Can “Location Verification” Stop AI Chip Smuggling?

US lawmakers propose a new system to check where chips end up.

US export controls are meant to keep advanced AI chips out of rival hands — but tens of thousands slip through each year. A new bill aims to change that by checking where these chips end up.

US Senator Tom Cotton (R-AK) introduced the Chip Security Act on May 9, which, if enacted, will require “a location verification mechanism on export-controlled advanced chips.” A bipartisan House companion bill was introduced on May 15 by Representatives Bill Huizenga (R-MI), Bill Foster (D-IL), John Moolenaar (R-MI), and Raja Krishnamoorthi (D-IL). These bills were proposed as the Trump administration works toward replacing the Biden-era diffusion rule, which set up a tiered system governing countries’ access to AI chips exported from the US. Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) Director Michael Kratsios recently called for “strict and simple” export controls, while White House AI and Crypto Czar David Sacks said that a “trust but verify” approach was needed to prevent diversion of AI chips to China.

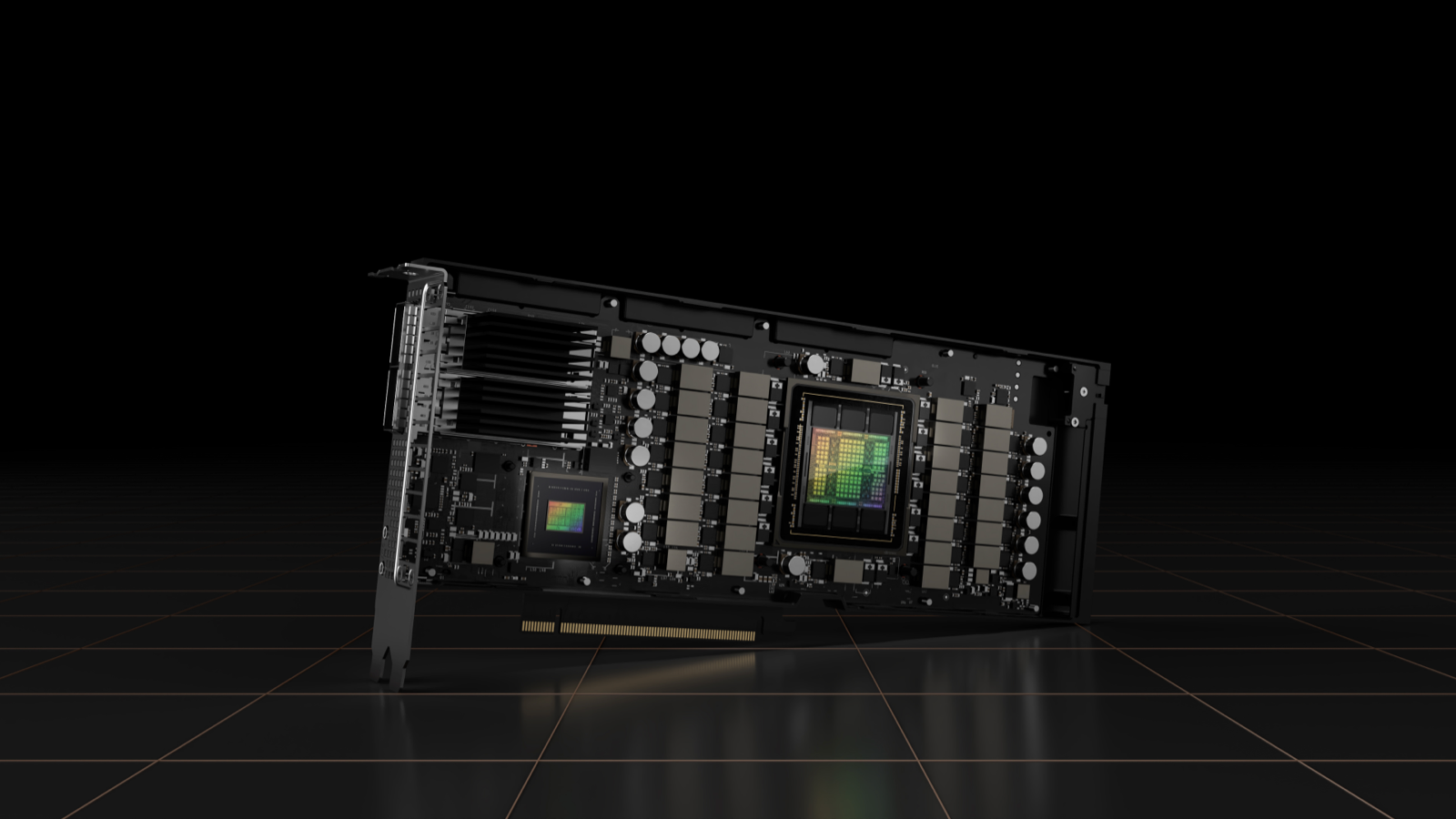

The US first introduced export controls on AI chips in 2022 to restrict China’s supply of the most advanced AI chips, allowing the US to maintain a technological edge and restrict military applications of AI. These controls target specialized chips like the H100, which are utilized for advanced AI development — not standard graphics processing units (GPUs) used in personal gaming PCs.

Want to contribute to the conversation? Pitch your piece.

An estimated 100,000 export-controlled GPUs were smuggled into China last year, according to an upcoming report from CNAS, the Center for New American Security. But that number is very imprecise, ranging from tens of thousands to one million depending on assumptions in the model to make the estimate. For reference, DeepSeek claims to have 10,000 Nvidia GPUs. However, other reports estimate their stock at around 50,000. Erich Grunewald, an associate researcher in the compute governance team at the Institute for AI Policy and Strategy (IAPS), told The Economist that he estimates smuggled chips represent “between a tenth and a half of China's AI model-training capacity.”

Oftentimes, these chips are sold to shell companies in countries not affected by export controls. The chips then find their way through smuggling channels into China or other restricted countries, evading export controls. A New York Times report found a market vendor arranging a shipment of chips in Shenzhen worth over $100 million. Bloomberg reported on a deal in which, over the course of six months, more than 8,000 AI chips worth $300 million were smuggled to Russia via an Indian pharmaceutical company.

“Right now, there's no reliable way for the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) — which creates US export controls — to know where these chips will end up after the initial export,” Tao Burga, Technology Fellow at the Institute for Progress, told AI Frontiers.

Senator Cotton’s bill aims to address this blind spot. By verifying the location of AI chips, regulators can more easily identify suspicious activity for investigation, enabling them to direct their limited enforcement resources more efficiently.

While the bill does not specify a particular approach, some experts argue for a delay-based location verification system. This does not rely on GPS, as GPS is not sufficiently secure against spoofing attacks that could manipulate chips’ apparent location. Also, satellite GPS signals often can’t penetrate the walls of data centers where AI chips are housed.

Instead, delay-based location verification involves a series of “landmark” servers set up in data centers distributed around the world. These landmarks would send signals to AI chips, which would then respond. The time it takes to send and receive the response would be used to calculate the maximum possible distance of the chip from the landmark. A report released earlier this year and co-authored by former Google CEO Eric Schmidt argued for an approach along these lines.

Critics of location verification proposals have drawn comparisons to the Clipper Chip — a controversial US government proposal of the 1990s that mandated a backdoor for accessing encrypted communications. Advocates counter that functionality for location verification is not unusual and is found in consumer hardware such as iPhones, which can even be remotely disabled if stolen.

Those in favor of location verification also argue that there are implementations that are privacy-preserving. A delay-based location verification system, as proposed, would not provide any access to the data processed by the AI chip, according to Burga. “This would reveal nothing about what's going on inside the chip, nothing about what the customer's doing with the chip, not even where exactly the chip is,” says Burga.

Rather, the data proposed through a location verification system would provide coarse-grained information on chip locations. By triangulating across several landmarks, a rough estimate of the location of the chip can be obtained, enough to assess whether or not it’s still in the original country to which it was exported from the US, for instance.

There are also questions about the security of the location verification system aboard the chip itself. Could saboteurs disable the part of the AI chip that would allow it to receive and send messages to a landmark?

“Nvidia's public documents say that their secret key [which would enable the location verification system] is on-die. That means it's directly on the chip, and it's very small and difficult to remove,” says James Petrie, a compute security and governance specialist at the Future of Life Institute. Doing so would require highly specialized tools, but, given the stakes, a motivated actor may not be deterred.

In another concerning scenario, chip users might also try to tamper with the speed of messages that are sent from a chip to a landmark. If an adversarial state were to slow down the AI chip’s response, this would lead to an inaccurate reading and estimate of the distance between the chip and the landmark. However, this manipulation would likely produce a suspiciously broad range of possible locations — potentially spanning the entire globe — which could itself serve as a red flag for regulators, indicating possible tampering.

Even if it is not possible to make a location verification fully secure, it could still provide a valuable additional layer of defense. By offering an early signal of suspicious activity, it could enable faster and more targeted enforcement activity by BIS, raising the risk of getting caught for would-be smugglers and reducing the number of chips that are successfully smuggled.

How costly and time-consuming would it be to update chips so that they have these location verification mechanisms? Because the physical hardware for communication is already on the chips, Nvidia would only need to issue a firmware update that enables communication between the landmarks and an AI chip. “At least based on my experience as a firmware engineer [at Intel] a few years ago, I don't think it would be that much work for them to do,” says Petrie.

Nvidia has recently acknowledged that a system to transmit “limited telemetry—including information on location and system configuration” would be technically feasible to develop. Previous research indicates that it’s possible to achieve good accuracy globally with fewer than five hundred landmarks. More targeted landmark deployments around countries of concern for chip smuggling could likely be smaller and cheaper. Those implementing the scheme could use existing infrastructure, such as renting out servers from cloud providers, instead of building their own.

For chip designers and others in the supply chain, there are concerns that export restrictions are hindering American companies’ ability to lead global markets, creating a vacuum that Chinese producers like Huawei could fill. If location verification mechanisms can ease concerns about exporting US chips to countries with a higher risk of chip smuggling, they could facilitate deals to sell US chips to AI “swing states” — countries that maintain good relations with both the US and China.

Location verification isn’t a silver bullet for cracking down on smuggling. The agency tasked with enforcing export restrictions, BIS, is sorely underfunded. Even with advanced location verification, US regulators may struggle to enforce rules to prevent chips from reaching their illicit destinations without additional staffing and resources. Automated “geofencing” of chips which would deactivate or limit their functionality in unauthorized locations could help, but may require more extensive technical updates to AI chips to be secure.

But the reality is that we have limited knowledge on the smuggling market and the exact number of chips even being trafficked. So although location verification for AI chips is not a perfect solution to end all smuggling, it could still be an effective tool and a step toward knowing more about this hidden trade, helping underfunded regulators enforce restrictions that already exist.

See things differently? AI Frontiers welcomes expert insights, thoughtful critiques, and fresh perspectives. Send us your pitch.

The White House is betting that hardware sales will buy software loyalty — a strategy borrowed from 5G that misunderstands how AI actually works.

AI automation threatens to erode the “development ladder,” a foundational economic pathway that has lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty.